The Awadh region in Uttar Pradesh, India, is a land steeped in history, culture, and tradition. Known for its fertile plains, vibrant culture, and significant role in India’s past, Awadh has been a center of power, art, and rebellion. From its ancient roots in the Kosala kingdom to its time under Mughal rule, the Nawabs, and the British, Awadh’s story is one of resilience and richness. Today, it remains a cultural heartland, with cities like Lucknow and Ayodhya shaping its identity. This article explores Awadh’s journey through time, covering its ancient origins, medieval grandeur, colonial struggles, and modern-day significance.

Ancient Roots of Awadh

Awadh’s history begins with its connection to the ancient kingdom of Kosala, mentioned in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain texts. The region’s name comes from Ayodhya, believed to be the birthplace of Lord Rama, the central figure of the Ramayana. In ancient times, Kosala was a powerful Mahajanapada (great kingdom) between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, with Shravasti as its capital during Buddhist times. The region, nestled between the Ganges and the Himalayas, was known for its fertile lands, which supported agriculture and trade. Archaeological findings, like those in Ayodhya and Shravasti, reveal a thriving civilization with advanced urban planning and religious centers. Awadh’s early history is also tied to indigenous communities like the Bhars and Nishads, who lived along rivers like the Sarayu and Gomti, shaping the region’s cultural and political landscape.

Awadh Under Islamic Dynasties

By the 13th century, Awadh came under the influence of Islamic dynasties, starting with the Delhi Sultanate around 1350. It later became part of the Sharqi Sultanate of Jaunpur for nearly a century (1394-1478). The Mughal Empire absorbed Awadh around 1555 under Emperor Humayun, and it became one of the empire’s key provinces, or subahs, under Akbar. The region was divided into five sarkars, Awadh, Lucknow, Bahraich, Khairabad, and Gorakhpur, each further split into smaller districts. Mughal governors, or Subahdars, managed Awadh, but the region’s fertile Doab plains made it a target for power struggles. The Mughal era saw Awadh grow as a hub of trade and culture, with Persian influences blending into local traditions. By the late 17th century, as Mughal power weakened after Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, Awadh began to assert greater autonomy.

Rise of the Nawabs

In 1722, Saadat Khan, also known as Burhan-ul-Mulk, was appointed governor of Awadh by Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah. A Persian Shia from Nishapur, Iran, he laid the foundation for Awadh’s semi-independent rule. Saadat Khan reduced Mughal influence by reforming the jagirdari system, auditing revenues, and appointing loyal local officials. His successors, like Safdar Jung and Shuja-ud-Daula, further strengthened Awadh’s military and administrative systems. By the mid-18th century, Awadh was practically independent, with Faizabad as its capital. In 1775, Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula shifted the capital to Lucknow, which became North India’s cultural hub. The Nawabs were known for their lavish lifestyles and patronage of arts, poetry, and architecture, leaving behind landmarks like the Bara Imambara and Rumi Darwaza.

Awadh’s Cultural Golden Age

Under the Nawabs, Awadh became a beacon of culture and refinement. Lucknow, in particular, flourished as a center for poetry, music, dance, and cuisine. The Nawabs patronized Urdu poetry, with poets like Mir Taqi Mir thriving in their courts. Kathak dance and thumri music gained prominence, blending Persian and Indian styles. Awadhi cuisine, influenced by Mughal, Persian, and regional flavors, gave rise to dishes like biryani, kebabs, and kormas. The Nawabs’ love for grandeur was evident in their clothing, fine chikankari and zardozi work adorned their robes. Architecturally, structures like the Chhota Imambara and the Residency reflected a mix of Mughal and European styles. This cultural richness earned Lucknow the title of “Shiraz-e-Hind” (the Persia of India).

British Influence and Annexation

British interest in Awadh grew in the 1760s after the Battle of Buxar in 1764, where Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula was defeated. The Treaty of Allahabad (1765) placed Awadh under nominal British control, with the Nawabs paying tribute. By 1801, Saadat Ali Khan II ceded half of Awadh’s territory, including Rohilkhand and Gorakhpur, to the British under pressure. In 1816, Awadh became a British protectorate. The final blow came in 1856 when Lord Dalhousie, using the pretext of misgovernance, annexed Awadh and deposed Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. This act, justified by the Doctrine of Lapse, sparked widespread resentment. The annexation stripped Awadh of its sovereignty, and the Nawab’s lavish court was dismantled, fueling anger among locals.

Awadh in the Revolt of 1857

The annexation of Awadh was a major trigger for the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The loss of Awadh’s independence, combined with cultural insensitivity by the British, ignited uprisings across the region. Lucknow became a focal point, with the Siege of the Residency witnessing fierce fighting. Begum Hazrat Mahal, wife of Wajid Ali Shah, led the rebellion, proclaiming her son Birjis Qadr as the ruler. Local communities, including zamindars and sepoys, joined the fight. The rebellion lasted from July 1857 to March 1858, but the British regained control after brutal reprisals. Awadh’s role in the revolt highlighted its people’s resistance to colonial rule, leaving a lasting mark on India’s freedom struggle.

Awadh Under British Rule

After crushing the 1857 rebellion, the British merged Awadh with the North-Western Provinces, forming the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh in 1902. The region’s fertile lands were exploited for revenue, and British administrative systems replaced traditional structures. Lucknow remained a key city, but its cultural vibrancy dimmed under colonial policies. The British built railways and modern infrastructure, like Kanpur Central station, boosting trade but prioritizing their economic interests. Awadh’s people, however, continued to nurture their cultural identity, with Urdu literature and traditional crafts like chikankari surviving. The region also played a role in India’s independence movement, with leaders from Kanpur and Lucknow organizing protests and supporting the Indian National Congress.

Awadh’s Role in India’s Independence

Awadh contributed significantly to India’s fight for freedom. Kanpur, a major industrial and military center, was a hub for revolutionary activities. Leaders like Nana Sahib and Tantia Tope, linked to the 1857 revolt, inspired later generations. In the 20th century, Awadh’s cities, especially Lucknow, hosted key Congress sessions and non-cooperation movements led by Mahatma Gandhi. The region’s educated elite, including lawyers and writers, mobilized support for independence. Awadh’s rural areas, with their strong community ties, also joined protests like the Quit India Movement in 1942. The region’s history of resistance, rooted in 1857, fueled its commitment to ending British rule, culminating in India’s independence in 1947.

Awadh in Independent India

After independence, Awadh became part of Uttar Pradesh, with Lucknow as the state capital. The United Provinces were renamed Uttar Pradesh in 1950, and Awadh’s districts, including Ayodhya, Faizabad, Barabanki, and Sultanpur, remained central to the state’s identity. The region’s agricultural wealth, often called the “granary of India,” supported India’s food security. However, Awadh faced challenges like poverty and underdevelopment in rural areas. Politically, it remained influential, with constituencies like Amethi and Raebareli playing key roles in national politics. The region’s cultural heritage, from its cuisine to festivals, continued to thrive, with Lucknow’s markets and Ayodhya’s religious significance drawing visitors from across India.

Modern Awadh: Culture and Identity

Today, Awadh is a vibrant blend of tradition and modernity. Lucknow, its cultural capital, is famous for its Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, a syncretic culture blending Hindu and Muslim traditions. The city’s markets, like Hazratganj and Aminabad, buzz with Awadhi food, chikankari embroidery, and traditional jewelry. Ayodhya, a global pilgrimage center, has gained renewed attention with the Ram Temple’s construction, boosting tourism. Awadh’s cuisine, with dishes like galouti kebabs and sheermals, is celebrated worldwide. The region’s language, Awadhi, a dialect of Hindi, is still spoken in rural areas, preserving folk songs and stories. Despite modernization, Awadh retains its distinct identity, rooted in its history of art, poetry, and hospitality.

Political Significance of Awadh

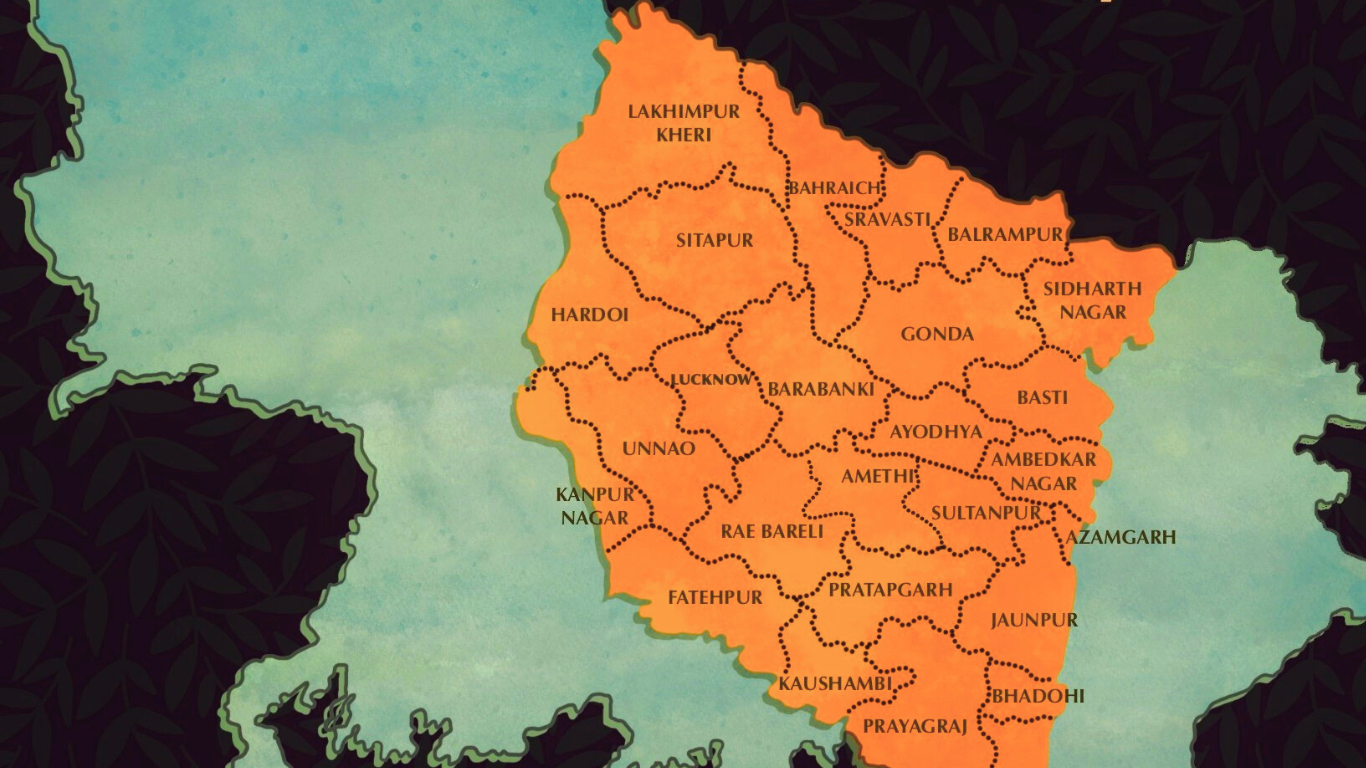

Awadh’s political importance endures in modern India. Its 25 districts, including Lucknow, Ayodhya, and Raebareli, are key electoral battlegrounds. The region’s diverse population, including Awadhis, Bhars, and Nishads, shapes voting patterns. Historically, Awadh’s political influence grew under the Nawabs and continued through the independence movement. Today, leaders from Awadh hold sway in Uttar Pradesh politics, with constituencies like Amethi and Raebareli often linked to national political dynasties. The region’s cultural and religious significance, especially Ayodhya’s role in national discourse, keeps it politically relevant. Awadh’s voters, balancing tradition and development, continue to influence India’s political landscape in elections.

Economic Importance of Awadh

Awadh’s economy has always been tied to its fertile lands, part of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Known as India’s granary, it produces wheat, rice, and sugarcane, supporting millions of livelihoods. Lucknow and Kanpur are industrial and commercial hubs, with Kanpur’s leather and textile industries and Lucknow’s IT and service sectors driving growth. The region’s connectivity, with major railways and highways, facilitates trade. Traditional crafts like chikankari and zardozi remain economically significant, employing artisans and attracting tourists. However, rural Awadh faces challenges like unemployment and migration. Government initiatives, like agricultural reforms and tourism promotion, aim to boost the region’s economy while preserving its cultural heritage.

Awadh’s Social Fabric

Awadh’s society is a tapestry of diverse communities, including Awadhis, Bhars, Nishads, and others. The region’s Ganga-Jamuni culture fosters harmony between Hindus and Muslims, seen in shared festivals like Holi and Eid. Rural Awadh relies on agriculture, with strong community ties, while urban centers like Lucknow are cosmopolitan. The region has faced communal tensions, particularly in Ayodhya, but its syncretic traditions endure. Education and literacy have grown, with institutions like Lucknow University shaping young minds. Social challenges, like caste disparities and rural poverty, persist, but Awadh’s people remain resilient, preserving their unique identity through language, food, and traditions.

Tourism in Awadh

Awadh is a treasure trove for tourists, blending history, culture, and spirituality. Ayodhya, with the Ram Temple and Hanuman Garhi, draws millions of pilgrims. Lucknow’s landmarks, like the Bara Imambara, Chhota Imambara, and Rumi Darwaza, showcase Nawabi architecture. Kanpur’s historical sites, like the Jajmau Tila, reflect its ancient past. The region’s festivals, like Lucknow’s Mahotsav and Ayodhya’s Deepotsav, attract visitors. Awadhi cuisine, served in iconic eateries like Tunday Kababi, is a highlight. The government’s focus on tourism, including heritage walks and riverfront development, has boosted Awadh’s appeal, making it a must-visit destination in India.

Challenges Facing Modern Awadh

Despite its rich heritage, Awadh faces modern challenges. Rural areas struggle with poverty, unemployment, and inadequate infrastructure. Migration to cities like Delhi and Mumbai is common among youth seeking better opportunities. Urban centers like Lucknow face overpopulation and pollution, straining resources. Communal tensions, especially in Ayodhya, have occasionally disrupted harmony. Agricultural productivity, while high, faces issues like water scarcity and outdated farming practices. The government is addressing these through schemes like smart city projects and rural development programs, but progress is slow. Balancing modernization with cultural preservation remains a key challenge for Awadh’s future.

Awadh’s Future Prospects

Awadh’s future looks promising, with its cultural and economic potential driving growth. The Ram Temple in Ayodhya is set to make it a global pilgrimage hub, boosting tourism and local economies. Lucknow’s development as a smart city and IT hub is attracting investment. Initiatives like the Purvanchal Expressway improve connectivity, fostering trade and development. Awadh’s traditional crafts and cuisine have global appeal, with efforts to promote them internationally. However, sustainable development is crucial to address environmental and social challenges. By leveraging its historical legacy and modern opportunities, Awadh can remain a vibrant region, blending its past with a forward-looking vision.